By Vidya Rajan, Columnist, The Times

In the fall, I spent a month in Japan. It’s an interesting country geographically, sociologically, and ecologically. Geographically, Japan is a comma-shaped stretch of some 14,125 islands to the east of the Korean peninsula. About 120 are inhabited, and five islands (Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and the tiny southernmost island of Okinawa) host 95% of the population. Although Japan spans a longer North-South dimension than East-West dimension, the major cities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Hiroshima are lined up pretty much from East to West. Overlaid on the United States’ East Coast, Japan would span from Newport, Vermont, to Mobile, Alabama. 66% of the country is forested. Much of Japan is mountainous, with over 18,000 named peaks and has about 110 active volcanoes,[1] the largest and most famous of which is Fujisan in the south of Honshu Island. An enjoyable byproduct of this volcanic activity are the many ‘onsens’ or natural hot springs, suitable for a fully immersed bath or a footbath.

In the fall, I spent a month in Japan. It’s an interesting country geographically, sociologically, and ecologically. Geographically, Japan is a comma-shaped stretch of some 14,125 islands to the east of the Korean peninsula. About 120 are inhabited, and five islands (Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and the tiny southernmost island of Okinawa) host 95% of the population. Although Japan spans a longer North-South dimension than East-West dimension, the major cities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Hiroshima are lined up pretty much from East to West. Overlaid on the United States’ East Coast, Japan would span from Newport, Vermont, to Mobile, Alabama. 66% of the country is forested. Much of Japan is mountainous, with over 18,000 named peaks and has about 110 active volcanoes,[1] the largest and most famous of which is Fujisan in the south of Honshu Island. An enjoyable byproduct of this volcanic activity are the many ‘onsens’ or natural hot springs, suitable for a fully immersed bath or a footbath.

Sociologically, 95% of the population is of Japanese ethnicity. This shared background and history seems to maintain strong social norms which prioritize harmony. Japan has a population of 125 million in a country the size of California; Tokyo alone has about 37 million people. By contrast, the United States has a population of 350 million spread out over 25 times the land area, and our most crowded city, New York, has about 9 million people.

Having experienced New York, I expected bedlam in Tokyo. But in Tokyo – and elsewhere in Japan – everything and everyone flowed by silently and smoothly. People moved about and around each other without any difficulty, trains and buses ran exactly as scheduled, buildings and streets were immaculate, the traffic was busy but orderly, parks and flowers were abundant, if pocket-sized. Everything is a miracle of space management and exquisite attention to detail.

My enduring impressions were: 1. How clean it was. No one dropped trash despite the absence of public trash cans (removed after a terror attack in Tokyo Station in 1995). If you remember back to the soccer World Cup in Qatar, Japanese fans cleaned up the stadium after the game, to universal commendation. In Japan, it is in the national character to be mindful of tidiness. One early morning in Kyoto, I saw the early morning street cleaning crew in action. One cleaner was scraping something off the street – the street! Maybe it was chewing gum. But that is the level of cleanliness I am talking about. The spotless variety of clean. 2. How quiet it was. No one spoke loudly in public or on the phone on the train. Tooting the horn in traffic even when discombobulated was unusual. Music never blared from passing cars or even when passing by homes or clubs. 3. How orderly it was. Everyone followed the rules. No one jaywalked even when there was no car in sight. No one walked around eating or drinking. No one jumped the line. On the flip side, no one noticed or intervened to help when I was standing in front of a map, looking lost and bewildered, as I did the first time I was in Shinjuku station, the busiest train station in the world. Everyone passed by in their own little bubble. Now, that would probably not happen in New York City.

Ecologically, a biologist will tell you that the island nature and splintered habitats can harbor give rise to highly localized species and enormous animal and plant diversity. There are lots of endemic species found only in Japan – “nearly 40% of land mammals and vascular plants, 60% of reptiles and 80% of amphibians” – according to the Convention on Biological Diversity.[2] Vertebrates include the iconic Japanese macaque, famous for sitting in onsens in the winter, the irascible Asiatic black bear which was depicted on a sign I passed as having a mouthful of knives (they kill about a dozen people a year) and the wild boar, which I am reliably told is classified as a ‘mountain whale’. The term is historical and ingenious: Buddhism does not allow eating four-legged animals, but the Japanese were fond of eating boar. To be Japanese and Buddhist and still eat boar…well, just re-name it ‘whale’, for it is a large mammal. For the same reason, hares are re-designated ‘birds’ since they have wing-like ears.[3] Other endemic vertebrates include the serow (an antelope), raccoon dog (its folkloric ‘tanuki’ version can be seen on a vase by the door of the new bonsai exhibit at Longwood Gardens), the red-crowned crane, and the giant salamander (which grows to 5 feet in length). Invertebrate diversity is immense. There are supposedly 30,000 identified insect species on the island, and estimates are that 70,000 more are yet to be described.[4] And, of the 125,000 species of Hymenoptera in the world, 4,500 are present in Japan.

The Hymenoptera are an ‘order’ of class Insecta, and include wasps, bees, ants and sawflies. All these animals undergo full metamorphosis from egg to larva to pupa to adult (technically known as holometabolous). If you have been reading Regina Rhoa’s excellent and informative PSBA column, Hymenoptera World, you will know that many wasps and bees are eusocial, that females have ovipositors modified to stingers, and belong in the group Aculeata. These animals have narrow “wasp” waists to allow their body to contort to deliver their sting. But wasps first emerged as carnivores eating other animals and/or using their ovipositors to inject eggs into unwilling living hosts. The potential prey did not take it lying down, and so some of these early wasps dabbled in getting additional protein from the pollen of newly evolved flowers, becoming the first pollinators. The benefit was that pollen does not run away or fight back like living prey do, and the plants quickly made nectar to encourage more visitations. Thus, pollinating bees were born.

The Hymenopterans relevant to this article are the families Vespidae (wasps) and Apidae (bees). Regina noted in her November 2024 article that all hornets are wasps, but that not all wasps are hornets. Wasps can be solitary or social. Of the thousands of social wasps, common wasp genuses are: Vespa (hornets), and the social wasps, Vespula and Dolichovespula. Both the latter are called “yellowjackets” but can have black, white or yellow coloration. Vespula have shorter faces and nest underground, and Dolichovespula have longer faces and nest above ground. There were plenty of wasps around in Japan, but I didn’t try and measure their faces or find their domiciles. Then to Vespa, the hornets. Hornets are larger than wasps and supposedly make teardrop-shaped aerial nests. I don’t think that all hornets have read the manual, because we had European hornets which took up residence in a hollow in a tree in our garden. But still, their larger size and copious venom makes them unwise to annoy.

One of the most astonishing of this group is the giant Asian hornet (Vespa mandarinia). I was fortunate enough to see two live hornets (they were locked together on the ground and did not seem to care that I was watching them.) The first thing about these animals is that they are HUGE. I have seen cicada killers (Sphecius speciosus) and European hornets (Vespa crabro) in my yard and Apis dorsata (rock honeybees) in India. These are all big, granted, at about an inch to an inch-and-half. The Asian giant hornet was about 2 inches long and stout, and there were two of them wrestling. I grabbed by phone to take a picture, but one of them flew away, and Figure 1 is a photo of the other one. It flew away sharpish too, so I didn’t get a chance to lay something down for scale.

Figure 1: Asian giant hornet (V. mandarinia) in Kanagawa prefecture, Japan. Approximately 2 inches long. Photo credit: Vidya Rajan

The giant Asian hornet is notorious for massacring managed Western honeybees (Apis mellifera) in their hives. Once a hive is located by a scout hornet, she recruits her sisters and they quickly lay the hive to waste. With lamentable tactics, the honeybees charge the hornets one by one, and they sequentially get decapitated. On the other hand, native Japanese honeybees, Apis cerana japonica, which evolved with the giant Asian hornet, use a different method. When a scout giant hornet locates a hive, a huge mass of native honeybees rush the hornet and ball it. Then they heat their bodies up and literally cook the hornet to death. To prevent their hives being attacked in the first place, native honeybees deploy two strategies. 1. They find cavities with entrances small enough for bees to enter, but too small for the hornets to get in. 2. They smear animal feces on the entrances. This oddly enough keeps the hornets out – perhaps, like the ermine, they do not like getting dirty. In any case, it repels the hornets and that is good enough. The giant Asian hornet’s sting is supposed to be pretty painful, but death is unusual unless there is anaphylactic shock. In Japan, about 30-50 people a year die from these stings. Their venom is not particularly venomous but the volume delivered makes it formidable.[5]

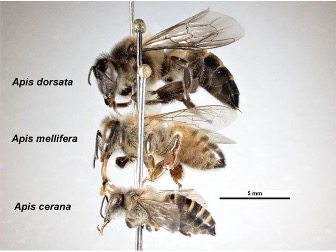

cerana appears to have come to Japan from the Korean peninsula, but their long isolation has caused them to speciate into subspecies japonica. This honeybee is smaller in size with more banding compared to Apis mellifera, the Western honeybee. The colony size is also smaller. When managed, these bees are housed in hives with movable frames or in lidded hollow logs in which they build immovable frames hanging from the lid. Intensive management for the ectoparasite Varroa or the endoparasite Nosema is not as necessary for A. cerana because they co-evolved with the mite and the microsporidian. For both, resistance mechanisms at the individual level which leads to tolerance at the hive level have been mooted. Resistance mechanisms would involve host-parasite interactions which are coevolving such as grooming and Varroa-sensitive hygiene (VSH). VSH behavior is such that the mites only enter drone brood, not worker brood. Additionally, drone cells have hard cappings and supposedly a sort of cap modification that prevents Varroa-infected drones from emerging from the cell. Resistance also takes the form of detecting and removing phoretic mites which camouflage themselves with cuticular hydrocarbons. For Nosema, removal of, or avoidance of contact with, infected individuals, who are recognized by changes in cuticular hydrocarbon composition takes place. Infected individuals may also age more quickly and therefore forage earlier (and die earlier) or show lack of homing ability or become weak, and therefore do not return to the hive. Self-medication with antibiotic and antifungal chemicals in propolis, honey and bee bread were also noted.[6] Small colony sizes and frequent swarming also help to manage parasite levels.

Figure 2: Three different Apis species compared. From: Wikimedia Commons.[7]

Finally, to an unusual traditional Japanese delicacy: wasp larvae. I came across a Splendid Table article about a village called Kushihara which hosts an annual festival where Vespula flaviceps larvae are the main attraction.[8] Before they are cooked, wasp nests are collected from the wild and raised in boxes where they are fed with sugar water, honey and chicken meat. There are prizes for the biggest nests and then the feasting begins. Wasp larvae are removed from the cells and pounded into a paste which is used to baste a rice cake on a stick. Sometimes adult wasps are also eaten. They even go after the giant Asian hornet’s larvae in a dish called osuzumebachi, and the adults are drowned in a liquor called shochu and the concoction is used as medicine.

That is the sting in the tale.

References:

[1]. Jma.go.jp. (2024). NATIONAL CATALOGUE OF THE ACTIVE VOLCANOES | TOC. [online] Available at: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/vois/data/filing/souran_eng/souran.htm

[2]. Unit, B. (n.d.). Main Details. [online] www.cbd.int. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile?country=jp

[3]. Nicol, C. W (1970). In praise of the ‘mountain whale’. [online] The Japan Times. Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2008/03/05/environment/in-praise-of-the-mountain-whale/ [Accessed 24 Nov. 2024].

[4]. Tojo, K., Sekiné, K., Takenaka, M., Isaka, Y., Komaki, S., Suzuki, T. and Schoville, S.D. (2017). Species diversity of insects in Japan: Their origins and diversification processes. Entomological Science, 20(1), pp.357–381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ens.12261

[5]. Conniff, R. (2003). Stung. [online] Discover Magazine. Available at: https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/stung [Accessed 24 Nov. 2024].

[6]. Kurze, C., Routtu, J., and Moritz, R. (2016). Parasite resistance and tolerance in honeybees at the individual and social level. 119(4), pp.290–297. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2016.03.007

[7]. Wikimedia.org. (2022). File: Apis species2.jpg – Wikimedia Commons. [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apis_species2.jpg. Reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

[8]. www.splendidtable.org. (n.d.). The Japanese tradition of raising and eating wasps. [online] Available at: https://www.splendidtable.org/story/2019/02/08/the-japanese-tradition-of-raising-and-eating-wasps