By Vidya Rajan, Columnist, The Times

Now that gardening season is underway, gardeners are drawn to plant sales and nurseries like a bee to honey. The general advice is to shun “invasives” and “exotic” plants, selecting instead “native”” plants to support local fauna. But what makes a plant, animal, fungus, a native? What is the generational number for drawing the demarcation line of from the other? In this article I want to take a look at the language we use to brand belonging or not belonging, starting with geographical and historical context, and then come back to plant choices that support the environment.

Now that gardening season is underway, gardeners are drawn to plant sales and nurseries like a bee to honey. The general advice is to shun “invasives” and “exotic” plants, selecting instead “native”” plants to support local fauna. But what makes a plant, animal, fungus, a native? What is the generational number for drawing the demarcation line of from the other? In this article I want to take a look at the language we use to brand belonging or not belonging, starting with geographical and historical context, and then come back to plant choices that support the environment.

When the Earth became habitable, it didn’t do so all at once. The land that makes up the continents emerged out of water about a billion years after the Earth formed, and the continents were shaped and arranged very differently from how they look today. Continental landmasses are parts of large tectonic plates, islands floating above the hot molten core of the planet. We live on the tippy tip of those islands. If you follow the continental shelf down, down, you will reach the ocean bed, which is seamed with hydrothermal vents which are conveyor belts sucking in ocean floor at some seams like the area between Australia and the Indonesian Archipelago and spewing them out in others, such as the mid-Atlantic Ridge. All the volcanoes dotted around the world are spewing-out centers, but they are not conveyor-belts; rather they are explosive belches which sometimes shoot out so much landmass that whole islands suddenly emerge. A small island – only a kilometer in diameter – emerged in Japan near Iwo Jima on August 13, 2021. The Hawai’ian islands, Galapagos islands, the Canary islands, islands in Japan, Iceland, Indonesia – all these were once seabed.

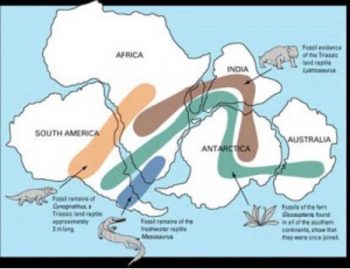

Continental landmasses changed beyond merely producing new islands. Whole continents merged and separated, and Alfred Wegener cut up outlines of the landmasses to fit them to each other like a jigsaw puzzle. Not only that, rocks and fossils also matched the landmasses as shown in Figure 1. The Lystrosaurus, had it been alive today, would have been a “native” of sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Antarctica. The Glossopteris plant would have ranged across all the landmasses of Gondwanaland. That they are extinct precludes the discussion. But what about those organisms that have persisted from 550 mya to today? Even just flowering plants, which originated late, at 250 mya, barely before the landmasses separated to each go their separate way. Would a plant extant in Gondwanaland and today’s South America, be considered invasive in today’s Australia?

Figure 1: Illustration showing similar rock assemblages and fossils across different continents that constituted Gondwanaland (550-180 million years ago).

Credit: Illustration reproduced from https://publish.illinois.edu/alfredwegener/evidence/ under Fair Use copyright law.

The answer obviously, is, it depends. Much acclimatization and adjustments have taken place since the landmasses separated into our currently distributed continents. Intercontinental travel since the 1400s has moved plants and animals willy-nilly around the world. It has almost certainly moved fungi, bacteria, viruses, and prions also, but they are not as visible unless they cause significant diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease of cattle (bacterium), mad cow disease (prion), COVID-19 (virus), Dutch elm disease (fungus). There was even a cartoon of an animal – an aphid, that destroyed French grape vines in the mid-nineteenth Century.

There are countless benign, even beneficial, transfers that take place. The honeybee is not a native animal to the great North American continent, nor are European Lumbricidae earthworms[i], or a slew of other earthworms imported from other parts of the globe. Both were initially transplants from Europe – one was intentional, the other unintentional . Both are now lauded as good citizens, but they may have caused enormous disruption before settling in to be productive. The earthworm undermined soil structure, damaging millennia-old forest ecosystems[ii], causing soil to loosen, toppling trees, changing the flora that grows, and displacing millipedes and other detritus-munching soil animals that suddenly saw a lot more competition for their food.

Figure 2: A cartoon from Punch from 1890: The phylloxera, a true gourmet, finds out the best vineyards and attaches itself to the best wines. Reproduced from Wikipedia URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_French_Wine_Blight. Image in the Public Domain.

In a conversation I recently had with Dr. Douglas Tallamy, who has begun the movement called “Homegrown National Park”[iii] to support biodiversity, he suggested replacing the terms “native” and “non-native” with contributors and non-contributors. Contributors, no matter the duration of their domicile, integrate into the ecosystem in a productive manner. Non-contributors displace the contributors while not integrating into the food chains.

The goal, then, is to make everything we plant in out gardens a contributor and good citizen, just like a honeybee or an earthworm.

[i]. Schult, N., Pittenger, K., Davalos, S. and McHugh, D., 2016. Phylogeographic analysis of invasive Asian earthworms (Amynthas) in the northeast United States. Invertebrate Biology, 135(4), pp.314-327.

[ii]. Hale, Cynthia Marie. Ecological consequences of exotic invaders: interactions involving European earthworms and native plant communities in hardwood forests. University of Minnesota, 2004.

[iii]. Homegrown National Park at https://homegrownnationalpark.org/