EPA, State DEP sediment containment rules could hit budget hard, officials say

By Mike McGann, Editor, The Times

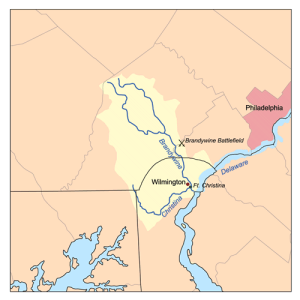

New rules for sediment containment could hit local communities in the Christina River basin (pictured above) hard in the coming years. East Marlborough officials said Monday that it could cost the township more than $500,000 over the next five years to meet the requirements.

EAST MARLBOROUGH — Township officials are trying to figure out how — and even if they can — comply with tough new federal and state requirements regulating storm water runoff and sediment control that could cost the township more than $500,000 over the next five years and potentially millions more down the road.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) are requiring municipalities to limit sediment erosion into local streams as a condition of renewing storm water runoff permits.

What this means for the township, officials say, is that the township is expected to reduce the sediment load into the Brandywine and Red Clay creeks by more than 875 tons over the next five years through various forms of storm water runoff containment and remediation.

While there have been some murky hints in recent years that the requirements would be coming, the stark reality of the situation was detailed Monday night by township engineer Jim Hatfield, during the monthly Board of Supervisors meeting.

The new DEP rules, spurred by EPA, would require the township from stopping some 875 tons of sediment per year from entering the Christina basin. The new permitting standards are requiring the township to accomplish between 10 and 15% of that number in the next five years. The problem is that the gains must come from what DEP terms “urbanized areas” — sections of the township that already largely have modern storm water runoff controls. Areas such as the Unionville village area and Cedarcroft, which have no runoff basins, cannot be used to meet the requirement.

“Going through this exercise without improving the quality of storm water runoff is frustrating,” Township Manager Jane Laslo said. “If we really wanted to improve things, we’d attack the areas with no basins.”

Originally, Hatfield said, when he reviewed the requirements he thought it might cost more than $3 million to comply — which he acknowledged would be impossible for the township to pay for, as it currently has an annual budget of less than $2 million. But after careful study and analysis along with his colleague, Neil Carlson from Vandemark & Lynch, Hatfield said they were able to reduce the cost to about $550,000.

The focus, Hatfield said, will be in three areas: refitting existing retention basins, building swales along roadways and using plantings along waterways to reduce erosion.

“It’s a bitter pill to swallow,” Hatfield said, noting that the proposed costs are about 5% of the township’s operating budget.

He asked supervisors if they could not commit to spending the full amount to give him a number they could live with and he would revise the plan accordingly and see whether or not DEP accepts the plan or rejects it. He said because the DEP would have evaluate more than 1,000 such plans statewide, and a large number coming from financially distressed communities, it could be a while before the township is even notified whether the township would be allowed to go with a slower and less costly remediation plan.

“Many municipalities are going to have trouble meeting this burden,” Hatfield said.

“I see a lot of potential problems with this throughout the commonwealth,” Supervisor Robert Weer said.

“What if we just tell them ‘no’?” Supervisor Eddie Caudell asked.

Hatfield said it is unclear what the enforcement would be, but likely fines would be assessed once it was determined that a municipality was stalling the process.

The township must decide a final path shortly, as the permit must be filed on Sept. 12.

“This is just another example of big government sending down requirements without financial support,” Weer said.

The sediment has become an issue in local waterways such as the Brandywine, Red Clay and White Clay, all of which feed into the Christina River, which in turn feeds into Chesapeake Bay. Because of additional sediment build up, flooding events have increased, particularly south of the local area — but sediment collection is evident in some areas locally — a sand bar like collection is visible in the Brandywine from the Route 926 bridge, a dirt area that increasingly becomes an island during low water times and appears to restrict the flow and volume of the creek.

Mike, the last paragraph you indicate the Red Clay and White Clay feed into the Christina River which in turn feeds the Chesapeake Bay. Doesn’t the Christina feed the Delaware River and then into the Delaware Bay?

This sediment build up is an increasing problem at many area bridges. I know the Bridge on 842 over the east branch of the Brandywine has a huge island in the middle that is making the river wider than the bridge. Each passing storm gets worse and worse to the point where the bridge isn’t going to be able to stand.

Good point. I must have misread the EPA stuff. Looking at the map, the Christina appears to run near or around the Elk, which does run into the Chesapeake, but the Christina would have run in two directions, which it cannot. Still, the efforts to clean up the Chesapeake led to these new EPA rules —